Coaching tricks for hypermobile chicks (and guys too, of course)

Whether you are hypermobile, or you are a coach who may train a hypermobile client, these 4 tips are absolutely essential for building a solid foundation and preventing potential injury and frustration.

[Read time: 15-20 minutes]

I’ve written previously on lifting and hypermobility, as it is a topic close to my heart. In this blog post, I want to continue the conversation. If you need a brush-up on the basics, check out the first post linked above.

Knowledge is not much without application, so the intent of this post is to enable you, the lifter or coach, to better understand the needs of hypermobile lifters and avoid common pitfalls: joint stress/pain, strength “walls,” cueing needs, understanding positioning for getting muscle tension, and training stability or stiffness appropriately. You’ll also get a ton of coaching principles I am learning, using hypermobility for context.

Probably more than you bargained for. 😉

A Quick Overview of Hypermobility

Hypermobility means joints that easily move beyond the normal range expected for a particular joint. It is estimated that 10-15% of normal children have hypermobile joints. Hypermobile joints are sometimes referred to as “loose joints,” and those affected are often referred to as being “double jointed.”

Women and certain ethnic groups are also statistically more prone to hypermobility. Hypermobility also has genetic factors, with a predisposition to hypermobility being passed on through specific genes. The baseline level of flexibility you are capable of is pretty much determined at birth. This doesn’t mean it can’t improve, but if you can’t get your foot over your head as a kid, chances are you won’t as a adult. This is why some people need a lot more flexibility work. Mobility work, on the other hand, everyone needs. Mobility is being able to control your ROM in a variety of tasks. “Hip mobility” refers to your hips being able to work to their full potential. But baseline hip FLEXIBILITY might mean one person can do a split, but another never really will. Their hip structure, or genetic potential for ROM in the hip, is not something you will affect with stretching.

For anyone, we want to use flexibility in an advantageous way to training. This is especially true for hypermobile lifters, whose joints are more at risk.

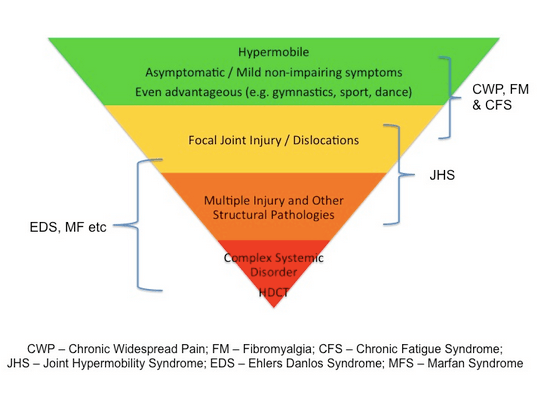

Extreme examples of hypermobility and strength/muscular control can be found in gymnastics and dance. Their joints have the ability to move through a larger range of motion with incredible precision, power, and speed. Hypermobility syndromes vary from useful and beneficial to sport, to debilitating and painful; hyper mobility is often a feature of more serious medical conditions (Ehlers-Danlos, Marfan Syndrome, Down Syndrome), as shown in the pyramid above.

How you use a physical quality will determine if it’s good or bad per se for an individual. It’s not one or the other, it’s merely a factor to consider. And consider it you should! I am not qualified to discuss specific medical issues, so this discussion on hypermobility is much more general and targeted to the lesser forms that are pretty common in the lifting population I interact with and train.

The 9 point Beighton Test will give you an easy way of determining your own or another’s hypermobility, but keep in mind that it only covers a relatively small number of joints. Similar to the FMS, it’s a tool, but not a fully comprehensive one from an assessment standpoint.

On a more personal note, some of the ideas I share here will be subjective, personal anecdotes about myself or clients, so please take it as such. While some things will be easily recognizable as supported by research or common knowledge, other ideas may not be, simply because no one has done a study on it, or I haven’t come across it, or I am working through theories that I might change my mind on later. I don’t know what I will know 10 years from now, but it will certainly be more than I do now.

So, this is my coaches’ perspective that needs to be filtered through your common sense and the needs of yourself and your clients or athletes.

Without further ado, let’s get into the details of these coaching thoughts for hypermobile lifters.

1.) Range of motion is on a much larger spectrum

“It’s not if you can do it, it’s how.”

If I could sum up one sentence that epitomizes coaching those with hypermobility, it’s that one; your joints have the capability, you can easily get into almost any position. But it takes a good coach and practiced eye to see how you are getting yourself there, and how the body is handling the load, not just that you can. This is even more important for hypermobile lifters because they CAN. And they can EASILY. At least initially. It is also very important simply because it takes time for joint, ligaments, and soft tissue to exhibit negative stress or pain. Which is why I say:

“Your body will always attempt to do what you ask it to do. What you get from it, depends on how you do it.”

(Wow, that sounded almost exactly the same as my last one-liner.)

A hypermobile lifter won’t necessarily know where to “end” a movement or how to do a movement with good muscular tension or “stiffness” (the good kind). Just having the range of motion doesn’t automatically mean that range of motion is productive to the qualities you want to develop. This means good coaching, and technique is necessary especially for compound moves that require multiple coordination between joints, much less when adding increased load, speed, and power!

Hypermobile lifters will often be able to go through the FULL range of motion easily (ass to grass squatting is no big deal), but spend more time stressing the passive tissues and joints than stressing the muscles. What I like to call “hanging out on your joints”.

Hypermobile people don’t necessarily have poor body awareness, but they can take their joints to further extremes, and this is not always appropriate and can result in a lot of joint stress rather than muscular stress.

Think of it this way; the first load you place on yourself is your own bodyweight! Anything in addition to that (external load) or any other kind of strength stress (isometric or bodyweight exercise) requires that you first support yourself (postural integrity), and that you can maintain that while you exercise. A breakdown in posture or muscle tension means a breakdown in technique. In any kind of exercise, you always want to be kind to your joints and build resiliency as you build athletic qualities. Hypermobile people may have less awareness as to HOW they are supporting a load on their body, or their baseline postural endurance/integrity may need to be built up before significant loading.

Let’s use an example.

Here is a pic of me locking out a squat. I was just filming myself with basically no load (barbell), to see my own patterns.

I would finish all my squats like this with such an aggressive lockout of the knees and hips that I would almost jump off the floor even with 225 lb. on my back. The reason I was filming at this instance (along with many other times) was a frustration as to why I felt basically constant SI stress.

Was this a show of immense athleticism? No. In this example, it was a misinterpretation of lockout “tension”. While I was squeezing my glutes hard, and “keeping my chest up” my alignment was way off ^. You can imagine how this could contribute to my SI joint becoming REALLY stressed out over time.

It’s important to note that you can’t ONLY go by what a lift looks like, especially if you are less experienced in coaching others or even figuring it out for yourself. There’s also: Feel (What muscles do you feel? Should be an open-ended question to help evaluate), smoothness (How coordinated does a lift look? What about breathing? Bracing?), intensity of load (Does a pattern change significantly with heavier or lighter weight?), etc.

For this example though, my squatting pattern went past the point of appropriate muscular control of my ROM in both the hole and the lockout. I had no sense of where the end should be, and what that felt like to my body, so I went to MY end. But as a hypermobile lifter, my end was too far (briefly envision the history of my body as well, including babies, knee injuries and how that might affect my perception of ROM, and my motor patterns at that point in time). I would lock my knees aggressively, but instead of sending the stress to the quads, it got sent to the backs of my knees. I squeezed my bum hard to “extend the hips,” but because my posture was so flexible, I would instead tuck and slouch my hips under me. Sticking my chest out translated into arching my lower back and flaring my lower ribs more than flexing the upper body musculature and maintaining core tension. My body’s interpretation of the cues I knew for squatting had a much broader range. Eventually, lifting was regressed to what didn’t hurt. Which is a sucky place to be. My body became extremely stressed in movement (I only had “stability” in certain positions), and while I still had “looseness” and “flexibility” relative to others (and always will), my body always felt stressed simply because my technique was not allowing my structure to support “load” very well, both posturally (without external load) and with external load.

Even when other coaches would tell me not to bounce out of the hole or to lower my ribs or to lock out the hips, those cues were relatively meaningless to me. It took me quite a bit of a run-around to understand what it MEANT in my body. This is, in part, why I think a lot of people get so overwhelmed with lifting form advice. It can be completely arbitrary to that person. (But more on that in the next points.)

Now, lifting like this for a couple of years, with lots of weight, and you might begin to understand (in part at least) why my SI joint gave me constant trouble, and I also had a hard time LOOKING muscular even though I lifted heavy. A build up of pain, and joint issues muddled the movement maps in my head, even when nothing was really structurally wrong with me.

I trained poor motor patterns very aggressively with some success because:

- I could, in the beginning. I did get benefit from it, make no mistake, but a lot of the benefit was professional (shitty athletes make better coaches?) not athletic per se. Technique, technique, technique. Relearning a pattern is much harder! How many people have to “stop lifting” or lose variety in movement expression throughout their exercise career?

- Strength is a neural quality, and you can strengthen a pattern much quicker than you grow the muscle to support it at heavier and heavier loads or with more complexity.

Greg Nuckols in his new e-book with Omar Isuf “The Science of Lifting” says:

“Strength is a skill. A lot more goes into picking up a heavy barbell (or insert some strength skill you want to do) than meets the eye. For this point, the most important factors are neural ones. Obviously, the size of your muscles is important, but if you take two people who are exactly the same in every way, and one has a more mechanically efficient motion they can activate more efficiently, they’ll lift more weight. To lift a heavy weight efficiently, you have to have the motor pattern stored in your brain, it has to be processed and coordinated with outside inputs by your cerebellum, and the right motor neurons need to fire, in the right order, very powerfully to both move the load and stabilize your joints. Ideally, this should all be done without any conscious thought; when you have to consciously think your way through a movement, your performance suffers and the likelihood of error increases.”

Stuart McMillan says this about developing maximal strength (which is the primary focus of powerlifting based programs that revolve around The Big 3):

“The first fundamental observation regarding maximal muscle strength is that unlike many of the mechanical muscle properties related to explosive muscle force production, maximal muscle strength is highly trainable in nearly every type of athlete. Even more so than the capacity to develop muscle hypertrophy, one could argue that nearly everyone possesses the capacity to gain maximal muscle strength.”

To really benefit from compound lifts, you first have to know what “a good motor pattern” for the movement feels like! It’s takes learning. Oftentimes we don’t realize we’ve learned something incorrectly, till we are suffering the consequences.

I’ve seen plenty of people doing barbell and kettlebell lifts with relatively “impressive” numbers, but does that mean strength? What is being strong?

Strength is not just weight on a bar. Strength is how your body expresses force and controls its movement with grace in a variety of tasks – maximal strength being just one expression of strength. And when we are talking lifting for those with hypermobility, training maximal strength COMES after you teach the body how to create muscle stiffness, tension, maintain posture, balance, and body awareness (controlling your own limbs)!

Understanding how ROM affects hypermobile lifters leads into the next practical training tip.

2.) Stability, stability, stability; isometrics, eccentrics, and stiffness

What is “stability vs mobility”? Gray Cook’s joint-by-joint approach uses this framework, which I find useful to describe the “needs” of each joint. Gray Cook says:

“The first thing you should notice is the joints alternate between mobility and stability. The ankle needs increased mobility, and the knee needs increased stability. As we move up the body, it becomes apparent the hip needs mobility. And so the process goes up the chain –a basic, alternating series of joints.”

Stability allows for mobility. Stability is a PRErequisite to mobility.

Let’s go off on a super brief tangent for a second. Bear with me.

The primary need of your body is survival. Everything comes back to that. From stress management, to diet, to training, survival and protecting its valuable organs, energy reserves, and LIFE is what matters FIRST. When I say “body,” it’s not really distinct from “you,” though it can be helpful to speak of our bodies in third person. But your body IS you.

What does this have to do with stability? Your spine and your brain. You will protect your spine, brain, and vital organs FIRST. That means balance, body awareness, and CONTROL are of primary importance for training success. That is the foundation.

So you are swinging a kettlebell around, cause you heard it would increase your hip power, give you an ass, and train you anerobically? Look at this pic below, what do you think the “body” is “saying” in the first pic vs the second?

Hypermobile = more mobile than average. So it makes sense that training for stability or better stiffness and muscular tension would be a good idea for those with hypermobility, perhaps even before they can benefit from large, compound movements even, and definitely before any type of speed and power activity. For this, isometrics are a great starting point. Why?

Isometrics teach you about stability in a snapshot of time, so I use them a lot more as a teaching tool for helping someone grasp their own positioning and force production – the HOW of generating force. Geoff Girvitz at Bang uses a variety of isometrics, and I’ve added quite a few of his variations. You can get creative with isometrics, because the intent is simple; create muscle tension with a good position, or a position that stresses the muscles you want someone to feel.

Isometrics on their own have limited value in the grand scheme of athleticism simply because in exercise, movement, and sport, we are not often called upon to rigidly hold a position while creating muscular tension. It’s not very functional per se, to use a common term. But, isometrics can be very valuable, especially for learning positioning, increasing time under tension (necessary for muscle hypertrophy), fixing “energy leaks” at certain points in bigger movements, or just helping someone understand what generating force with good form is in certain positions.

Your body doesn’t “know” muscles, it knows movement! Isolation exercises, isometrics, etc., fit into the bigger picture very well when you use them appropriately, and for hypermobile lifters, (and also those with poor body awareness and motor control) they are, dare I say, essential.

I will often have a client hold an isometric and then test the durability and stability of their position by trying to move them or tip them over. If you can resist my attempts to move your position as you apply muscular force against something or just against yourself (hold a bodyweight squat), you are doing a good isometric. This is often how I teach this, even to clients that have a physical advantage over me (men). Applying force is about leverage and positioning. Otherwise, I will move you, being much smaller or even technically “weaker.”

Bodyweight exercises can be useful, but only if you understand the positioning, the muscle tension, and how to control your range of motion. Otherwise, everyone who did burpees and pushups would get incredibly muscular and fit.

For instance, teaching someone how to stabilize their shoulders:

Have them stick their arms out in front of them without any further instruction. Tell them to resist your attempts to push them down without changing their posture (good way to also see how they will try to stabilize and where. Do they lean back? Forward? Hunch? Collapse in the waist?).

Then instruct them how to set their scaps, pinch their lats, relax the elbows, but hold tension in the arms.

NOW try and push their arms down. If they set their shoulders and hold tension appropriately, they should be able to resist you even with such a long lever (arms).

I use this all the time with clients! Super useful.

To take the idea even further from there, you can understand the principles behind basic progression, even with someone who needs to train a lot of stability in order to get to the REAL goal of risk-free mobility. I say risk-free because hypermobile people can be more prone to joint stress and injuries. The goal is never rigidity in movement, hence the need to get tension in the right way, not just any way, and progress from there.

An easy framework for understanding progression/regression for almost any strength/conditioning exercise if the goal is stability and muscle tension:

- Reduce ROM (machines can be very useful for this).

- Lower their center of gravity (floor based, half-kneeling, etc).

- Isometric resistance against immovable feedback (floor, wall, stick) to understand tension and generating force.

The progressions should translate gradually to building a physical (in their body and head) understanding of how you maintain control in larger and more complex ranges of motion. Then faster, then heavier, etc.

The same can be said for eccentrics. Eccentric contractions are the “road” that gets you to the concentric (except in lifts with no eccentric component). HOW you lift a weight starts with how you lower it!

I explain this to my clients as:

To shoot a rubber band far, you must first stretch it! The eccentric phase is the preparation for the force to be produced. Training slower eccentric movements can help someone understand HOW they get into the position. Holding an isometric helps someone understand HOW they stabilize that position.

(There are lots of exciting thoughts I have about training eccentrics, but I’d go way too off topic.)

All about the how!

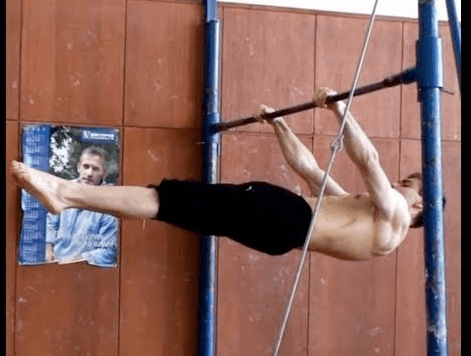

The body is smart is the sense that you can’t do movements well that require advanced stability, technique, and coordination unless you have it! Try cheating on a front lever. You can’t.

Your body will not let you do a front lever without stabilizing the spine properly, without core strength, alignment, etc. It would be impossible. The move is too advanced. BUT, what about exercises that DO allow you to get away with a variety of shitty technique? They require the same precision of balance, it’s just easier to get away with for longer.

Bigger range of motion means the NEEDS of hypermobile (or poor) movers trends toward learning stability and muscular tension maybe even before more compound and complex movements like a full barbell squat, a full power clean, a full pullup. Simply because they will not benefit from those movements unless their body can express them with proper technique. That is where you get the benefits from.

Currently, there is a glorification of “compound lifts” and “strength movements,” but strength is expressed in a myriad of ways. What strong MEANS in a body is entirely individual.

A strength movement can be a crawl. A strength movement can be a bicep curl. A strength exercise can be a barbell squat. Strength is simply what increases the body’s physical capabilities, and for that, there are so many options!

Practically, that means bodybuilding-type training (literally BUILDING up the muscles) and liberal use of isometrics and eccentrics, even before lots of “functional movement” type training (crawling, squat mobility drills, rope pulling, kettlebell swinging) may be more appropriate to really develop a physique and allow for harder and more complex movement challenges (muscle-up anyone?). A lot of your classic “strength training” is complex and hard to do correctly. That’s why it’s worth working towards! But for instance, kettlebell swings, while technically a power exercise, may not BE a power exercise for someone that has loose technique, no muscle stiffness, or doesn’t know how to create it.

A good idea for exercise choices for yourself and clients is: Make it super simple and super hard.

Not: “Make it super complex and compound and functional with tons of variety in one session.”

Benching with 10 lb. with good control and muscle tension can be more beneficial to someone than benching 55 lb., even if 55 lb. feels harder and temporarily allows for linear progression. This becomes even more important for those with hypermobility.

It’s all about the how.

3.) Filtering cues

Cueing is the words we say to get the action we want.

There are better minds that have delved into the science of cueing deeper than I have, so I will only briefly touch on this point Check out Nick Winkelman here in his 2 -part series.

“The goal of instruction is to prime the motor system by providing contextual understanding of the movement skill being learned. It should be noted that contextual understanding refers to the athlete’s ability to understand how to perform and self-correct a movement skill without feedback from a coach.”

I will paraphrase another coach I like, Kyle Evan Gentle (hot Olympic lifter FYI). He said:

“A cue is a personal thing between coach and client.”

A cue is nothing more than a tool to get a response. And there are principles for cueing that take into consideration the science of learning movement and producing a physical result from a verbal instruction (external vs. internal). The cues themselves, you could say, are basically arbitrary. Cues depend on the person you are cueing. As with everything, there is a better framework to worth within, but then within that is a massive realm of individuality and variability.

For hypermobile people, this ties into the first point. Cueing can produce a variety in expression of the movement you want them to do. Especially in overly aggressive cues; they may interpret cues physically in a more extreme manner.

“Chest out” could mean they end up overextending their spine constantly.

Aggressive cues might mean aggressive rather than appropriate ranges of motion. That’s about it for this point. But since you are working with a broader capability for interpretation of any one “cue” or “instruction.” use them wisely.

4.) Avoiding the grind: Tension vs. relaxation

Tension cannot exist without relaxation. For every thing that exists in the world, there is an opposite. Don’t train for excessive looseness by swinging the other direction and training excessive tension.

“Consistent progress is much simpler than you think, and takes much longer than you think.”

Building up real strength cannot be rushed.

Excessive tension (do you always feel tight?) makes for a stressed out body and “stressed out” looking movement. Just like a tight muscle is not a STRONG muscle. Muscles need to both contract and relax. Chronically tight muscles, chronic joint issues, and repeated aches and strains can often point to a disconnect between what you think will make you strong (squatting! pressing! kipping!) and what you actually need to get strong. (See point 2!)

Breathing or lack of, facial expression, grip, and joints tell a lot about tension, where you hold it, where it’s being sent (traps, neck and calves?) and what’s doing the work, so to speak. The majority of your exercises can be hard, but they should not be grindy.

What’s grindy?

Grindy = lots of work, effort, tension, etc., but no real adaptation taking place. You can work your heart out, and not get much from it. Why?

Because of HOW you work. There’s a theme here, eh?

Grinding reps frequently, is usually never a great idea for most people, but much more so for hypermobile and “loosey goosey” individuals. I say usually tentatively, because it depends on the grind context. In a general sense, a “good” grind should come from muscular effort without significant technique breakdown, and real grinders should be a relatively rare event. A “bad” grind is one where your body breaks down in posture repeatedly, or how you are training that motor pattern with that effort or load is not appropriate for you. You don’t PR everyday! Why are you trying to?

Matt Perryman in Squat Everyday describes this as “practice, not pain.” And that pretty much sums it up. You need enough practice that teases the line of ENOUGH, yet doesn’t consistently put you over that.

“In the culture of pain that is mainstream fitness, it hardly ever occurs to us that weight training can be about something else. … That you can improve without reducing yourself to a nauseous mess.”

I explain the difference types of “grinds” to clients, because you will get those lifts where THEY MUST push through it. A heavy squat might “pause” halfway up, and you have to have the intent to keep going UP and finish the lift.

But what that grind looks like determines if it’s good or bad in context. And sometimes a shitty grind for a PR is perfectly fine as well. But it shouldn’t be the norm. And for hypermobile lifters, grindy reps need to be avoided.

Repeatedly grinding reps should not be the majority of your training. Grinding reps for those with looser joints and less stiffness is asking for trouble.

On the other hand, you can’t know what “hard” is if you grind through everything and build up so much noise in your lifting, moving, and exercising that the definition of hard vs. easy vs. intense vs. smooth gets all mashed together. There should be distinction between efforts. This is the basis for programming right? You can’t have the same output everyday. You cycle between hard, medium and easy.

For true intensity, you must also know how to relax. This ALSO means that the bulk of your training should only tease the line of full effort/intensity ENOUGH to produce positive adaptations, with some occasional extremes, but not so much that you are basically constantly expending a ton of effort, tension, and the appearance of intensity without being able to distinguish between varying levels of effort.

Why do we talk in terms of percentages of a max? Because we need a way to scale our effort. But a 1RM only applies to a trainee that HAS ONE. Having a true max comes after training a solid base of strength with good technique. Having a 1RM at 185 in a squat, when you squat pattern is not so great, and you are dealing with repetitive joint stress means maybe that 1RM is simply useless as a measure of your fitness.

True mastery is EASE and GRACE in a movement, even when it’s “hard”, and requires as much relaxation (mentally and physically) as it does hard work (physically and mentally). The best stuff happens from periods of high tension, high relaxation balance that gradually pushes your athletic boundaries higher and higher.

Make it simpler, and make it harder. You need lots of practice that doesn’t muddle every effort together.

In Conclusion

If you are hypemobile or train those who are, keep in mind these factors when designing programs:

Don’t abuse their ROM. Use progressions that emphasize control of ROM. Increasing ROM is also progress, not just loading ROM.

Train for stability, and use isometrics and eccentrics to not only get time under tension, but help them learn proper positioning for force production in a variety of exercises. This will translate well later on to more complex movements, speed, agility, and power. This is an essential part of your foundation for long term success in any physical endeavor.

Watch carefully how someone filters a cue you use and adjust as needed. Familiarize yourself with the science of cueing, especially if someone has a hard time physically understanding certain movements, creating muscle tension, or self-evaluating/correcting their own technique.

Avoid the grind. Almost always. Excessively effortful, frequent exercise can build up “noise” in the body and make it hard for someone to know what good form, intensity, and effort MEAN and what those feel like FOR THEM and distinguish between levels of effort. You can’t always be at a 10. This can be a culprit in someone frequently hitting walls in their training or being unable to self-regulate their programming, self-correct technique and get a better sense of the tension/relaxation relationship. You need to know when to push and when to back off. HOW you know that, is based on some of the ideas outlined here.

Lastly, for an excellent philosophical read on strength training, especially in lifting, I highly recommend Squat Everyday by Matt Perryman.

• • •

Next: Are you Gumby? Hypermobility, Joint Laxity, and What’s Bad About Too Much Flexibility →

Achieve your nutrition and training goals with Joy’s expertise and support.

Get started now

One Comment